First released 25 July, 2020. Available here.

Ani White: For this month’s Furious Political Thought segment, we’re interviewing Australian writer and anti-fascist researcher Andy Fleming, AKA Slackbastard. Welcome to the show.

Andy Fleming: Thanks for having us.

Ani White: Thanks for coming on. Can you give a basic definition of fascism and the far right, and anti-fascism or antifa for the uninitiated?

Andy Fleming: I can certainly try. From my perspective, I understand fascism to be a far right ideology, and the far right as a whole, is, or can be characterised by defence of inequality, which is often understood as being expressive of human nature. So, proponents of far right ideology maintain that human inequality is not only natural, but often something to be celebrated and cultivated in society. And very often, though not always, this assumes a racial character, typically some notion of white supremacy, and is usually also gendered, so there’s a certain idea about the ‘natural order’ in terms of race and gender, and so on.

As a more or less coherent ideology, fascism emerged in Europe in the early 20th century, and it emerged in response to revolutionary movements. So it can also be understood as a counter-revolutionary movement, which is intended to combat anarchism, communism, socialism and so on. It typically advances some understanding of society, very often meaning the nation, as being organic, as having a proper hierarchical order.

So there’s obviously been a lot of debate and discussion over the precise meaning of fascism, like many other common political terms, and like those terms it’s been much abused, but I suppose within scholarship, one concept that’s obtained some currency recently is that provided by Roger Griffin, who defined fascism as a form of what he terms palingenetic ultra-nationalism, and that’s a particularly vigorous form of nationalism which is predicated on some kind of national rebirth. So in his study of fascist ideologies and movements, that’s the kind of minimal definition that he arrived at.

In terms of antifa, I mean generally it means, well quite literally anti-fascist, which could be used to describe all sorts of people who actively oppose fascism. But it has another meaning, which is used to describe those who oppose fascism, but do so in a more militant or uncompromising fashion, especially by way of direct action, and without relying on the state, the cops, or the courts, in order to further this goal.

Derek Johnson: Yeah, here in the States, we often have to make the explanation to liberals and especially completely paranoid right-wingers who listen to the president and Fox News and everything, that antifa like the Black Bloc, is more of a tactic, and an organising principle, rather than an actual organisation, with a hierarchical leadership or something.

Andy Fleming: Yeah, I look it as being, in one important sense, a domain of action. So it’s a particular expression of a collective identity. And I think it was Mark Bray’s book, The Anti-Fascist Handbook, who described it as a pan-leftist movement. So it’s quite a diverse range of actions, but within a particular sphere of activity which is opposing fascism, so among anti-fascists you’ll find a variety of views.

And I think also in Trump’s employment of the term, and that of other reactionaries in the US and other countries, it’s kind of a free-floating signifier in a way. It designates all those forces which oppose his regime, and those of others like him. So it’s not, analytically laughs I don’t think anybody should look to President Trump for understanding, but it is important, and significant I think, that Trump has chosen this term to describe his political enemies. And I think it’s because there’s an understanding, an association between anti-fascism and chaos and violence and so on, that he really wants to invoke in order to essentially scare his base, and motivate them to vote, or to re-elect him.

Derek Johnson: Yeah do you think a part of it, of him focusing on antifa, is people like Miller and Steve Bannon and a lot of these alt-right and outwardly fascist and Nazi figures being part of this administration, that they like put this language into his ear and on his radar?

Andy Fleming: Yeah, I think so, I think it’s both his advisors and whatever he saw on Fox News last night, or what’s the new one he favours, OAN or something?

Derek Johnson: Oh God, OANN, yeah.

Andy Fleming: So, in that sense I don’t think Trump is an ideologue, he’s a narcissist, and he’s not a thinker. It’s whatever appears to be most immediately of benefit to himself and his regime. But certainly in the case of Miller and Bannon, and other fascist or quasi-fascist ideologues who’ve got the president’s ear, they would have, I would assume, a sharper understanding, and would also know that, and be worried by, opposition and resistance to the Trump regime and its forces. So there’s a political calculus at work which has a pragmatic dimension, and also a more acute understanding which is based on something approximating reality, which is that there is actually opposition, and it’s important to try and crush this opposition by any means necessary.

Ani White: And in terms of Australia, where you’re working, what are the main fascist and anti-fascist forces in Australia currently?

Andy Fleming: Well, I’d make a distinction between fascist forces that are organised, and present themselves in public, but more importantly perhaps in terms of culture and ideology, what it is about contemporary Australian politics and society that lends itself to expressions of fascist ideology and movements. So organised fascism remains a fairly marginal phenomenon, but you’ll find elements of fascist ideology being expressed in parliament, in media, in pop culture and so on. And that’s kind of the political space in which organised fascism germinates, and incubates, and flourishes.

So in terms of the organised fascists, you have quite small groups, one of which I’ve written about recently is something called the Lads Society, and it’s a consciously fascist and neo-Nazi organising project, which is attempting to capitalise upon the last five years or so of right-wing agitation.

So, in 2015, you had Reclaim Australia emerge, I described it as a kind of proto-fascist movement, it was about reasserting some mythological claim about an Australian essence which those who participated understood as being under threat from Muslims, and the left, and other political tendencies. So it was about re-establishing a certain conception of Australia as being largely white, and Christian, and reactionary. But many of those who were drawn to it were often older people, for whom this was their first political engagement of any real sort, and it was significant in the sense that it brought thousands of people onto the streets under this banner.

And one of the other things that it did it did, is it gave birth to another groups called the United Patriots Front (UPF), which kind of constituted itself, or tried to constitute itself, as a kind of political vanguard of Reclaim, so the most militant elements. It was, in some respects, formed on the basis that Reclaim Australia was opposed with counter-protests and so on, and they understood that there needed to be some form of opposition, an anti-anti-fascist organising element. It thrived on social media, so it had a Facebook page, and I think at some point at its peak, it attracted something like 160,000 likes, or followers, or whatever. So it had some significance on social media. Then, in 2017, Facebook deleted the page. And it was very soon after that the UPF basically collapsed. And it was a fairly unstable coalition of neo-Nazis, although they didn’t present themselves as such in public, and Christian fundamentalists. And they united around militant opposition to Islam and to the left, both of which they understood as being highly corrosive of Australian society.

So after the UPF collapsed, one of the things that happened is that those who were drawn to Reclaim and UPF entered into a period of consolidation. So they wanted to capitalise upon the momentum that had been brought about through Reclaim and UPF, and all their various activities. And that’s where the Lads’ Society emerged. And it kind of models itself on overseas projects like CasaPound in Italy, in Rome, it’s a social centre and an important part of the fascist ecosystem, political ecosystem in that part of the world. So what [the Lads’ Society have] done is organised to obtain leases on properties, warehouses in Melbourne and Sydney and Brisbane and elsewhere, which are meant to be essentially social centres, where young men (and it’s exclusively for men – no girls allowed)… undergo both physical training, so you know exercise and so on, and also ideological training. And it’s part of an attempt to develop some political infrastructure.

And recently, at the beginning of this year, the Lads launched the National Socialist Network, which is essentially just another Nazi group that produces propaganda and distributes it. One thing that’s interesting about that is, they’ve met, they’ve discussed, they’ve decided, “we’re going to call ourselves National Socialists.” And that’s a departure from previous years of practice, where they’ve consciously chosen not to do so, because they’ve had an understanding that Nazi, or National Socialist, is a term most people are repulsed by. So I think it’s interesting that they’ve taken this step.

And they’re also drawing on a number of other small groups that have emerged in the last few years, like Antipodean Resistance, which again modelled itself upon National Action in the UK, produced lots of outrageous and provocative Nazi propaganda, ‘gas the kykes’ blah blah blah, all the sorta stuff you’d encounter online, now being produced in the form of posters and stickers, and distributed, and put up at university campuses, and outside synagogues, and y’know, a fairly standard form of Nazi practice. So you’ve got that, and there’s various other groups which have been in existence for some years, this is on the neo-Nazi wing: so Blood and Honour, Hammerskins, Aryan Nation, all sorts of groups and I understand them as, they emerge and collapse periodically, what they reflect is the existence of a broader extremist right network. The names under which they travel are usually less important than the fact that they’re in existence, and the labels they travel under vary, but what it expresses is an underlying sentiment.

And then you’ve also got, on the extreme right, groups like the Australia First Party, which has been around for 30 or more years, which developed out of another previous grouping known as National Action, not to be confused with the English neo-Nazis. [Australia First is] a registered political party, so it has at least 500 members, it contests elections, and is a white nationalist party essentially. It’s interesting in the sense that it also disavows any affiliation to National Socialism, or Nazism, and tries to draw upon Australian labour traditions. So in some ways it’s kind of like an old school Labourism, so protectionist and pays lip service to workers and so on, but crucially wants to reinstitute White Australia Policy. You’ve also got elements like Pauline Hanson and her party [One Nation], which again, I wouldn’t necessarily describe as fascist but extreme right.

And I think also what’s happened in the last few years, and why terminology is sometimes difficult, is there’s been a certain mainstreaming of racist and xenophobic ideas, which are expressed not only by these tiny groups on the far right, but also find expression in mainstream politics. And along with that, I think partly as a result of the emptying out, or the hollowing out of major political institutions, we had the example a couple of years ago in New South Wales, where a group of Nazis decided that they would infiltrate and attempt to take over a branch of the Young Nationals. And they were reasonably successful in doing so, until they were exposed, and the Nationals were forced to remove them from the party. But in that instance, what we’re talking about is a small network of a few individuals who were able to determine that this conservative party, and its youth wing, were vulnerable to infiltration. It was a relatively simple matter for them to engage in entryism, and to take it over. And that sort of thing happens fairly frequently, I think it’s becoming more common, and meets with potentially more success, because these major political parties – the National Party is part of the ruling coalition in Australia – they’re hollowed out, so they’re vulnerable to these sorts of maneuvrings.

So in terms of the anti-fascist forces, I think it’s often identified with public protest, so you’ll find anti-fascists on the streets when Reclaim, or the UPF, or some other group, the True Blue Crew whatever, take to the streets, you almost always find people turning up in opposition. Beyond that there’s the ongoing work which myself and others engage in, which is principally monitoring, documenting, analysing and sometimes publishing the activities of these groups.

So there’s been a relative abeyance of far right mobilisations in the last couple of years, it seems to have peaked a couple of years ago, those racist and fascist mobilisations, and as a result there’s been less anti-fascist activity on the streets. But certainly there’s an ongoing online battle taking place, and that’s the stuff I’ve been engaged in for quite a few years.

Ani White: You mentioned a couple of times that explicitly fascist groups in Australia are small, and even less explicitly fascist, it’s not necessarily a mass movement in Australia. Why do you think it’s still important to actively oppose them? Because there are obviously people who would say, these are marginal groups so we shouldn’t be paying them attention.

Andy Fleming: Well, I think that’s for each individual to decide, I think it’s important though that that is an informed decision. So very often, I think, the dismissal of anti-fascism as being of [little] political utility is based on a misunderstanding of the reality. So, for example… when you have a figure like Fraser Anning in parliament in their maiden speech, or their first speech to parliament, making reference to the Final Solution, that was phrased in terms of a final solution to immigration or something like that, but it was a nod and a wink to a sector of his base. And it’s important understanding that case, around Anning assembled a group of neo-Nazis, who were recruited by him, and used that platform to push what they term the Overton Window, to expand the bounds of acceptable discourse in Australian politics, and were somewhat successful in doing so.

But what they’re also trying to do is, I mean if you understand Australian society as being a colonial settler-society for most of its history, since its foundation, or formation as a Commonwealth in 1901. One of the principle pillars of that establishment was the White Australia Policy, which dominated Australian politics for most of the 20th century. And the way I see it, that leaves a historical and political legacy. Those policies have, in a sense, saturated the society, a society built upon invasion and genocide, in other words there are currents within Australian society that fascists seek to capitalise upon, and those are enduring.

One of the reasons that Australia, in terms of its own political history, has not witnessed the emergence of a mass movement of the far right (with the possible exception of the New Guard in the 1930s which is another story), one the reasons that movement hasn’t emerged is because the State itself adopted many of the key policies you would associate with fascism: so notions of racial purity, of establishing a Fortress Australia, a White outpost in the Asia-Pacific region.

The other thing to take into account is that, in my own view, those sorts of ideologies and movements have potential. It’s important to act in ways that limit that potential. Figures like Hanson and Anning and others are, in some respects, laughable. Hanson and Anning are not intellects. A lot of the things they say are fairly absurd. But I think that’s also to misconstrue the appeal of fascism, which is that it’s not based necessarily, or in large measure, as part of a rational programme. The emotional, and psychological, and sexual dimensions of fascism are often underestimated. And also, on that basis, so is its appeal.

How people choose to employ their political energies is up to them, and the main thing is to do so in a way that’s informed. And more broadly, not just in Australia, but elsewhere in the world, I think we’ve witnessed the emergence, or re-emergence of movements that are right-wing and authoritarian. And I don’t think that’s happenstance, and I think it’s also a product of political and economic crisis. And… we have an ecological crisis, and the ways in which the State, speaking generically, is going to handle that is probably through resort to authoritarian means. In order to justify those forms of rule, it’s important that there be movements that, in principle, support authoritarian regimes. So I think, whether it’s in Australia or elsewhere, it’s important to place some attention on what’s happening locally, but also situated in terms of global trends, and I think if you look at those global trends, whether it’s Trump or Bolsonaro, or a whole range of other figures that have emerged recently, right-wing authoritarians, part of their task is to build bases of support in the public. And those are, I understand them as being necessary but not sufficient conditions, to allow for the development of more conscious and fully developed fascist politics.

And to my mind prevention is better than cure. It’s a good idea to try and monitor these things, to oppose them where it’s useful to do so, with some understanding of these dynamic movements that rise and fall, and whatever we can do to make sure they fall rather than rise is a good idea.

Ani White: What [links] do Australian far right groups have to far right forces in other countries?

Andy Fleming: Well, I guess in terms of the formal linkages, there’s relatively few. But the Australia First Party often refers to the right-wing nationalist group in European Parliament as being allied, there’s a fairly close connection built up over time with figures like Nick Griffin in the UK, with what used to be termed the Front National in France, Golden Dawn in Greece, and various other parties of the far right around the world.

And also in the last few years, the internet is ubiquitous, and fascists use that as well as, or better than anyone else. If you look at a group like Antipodean Resistance, which I referred to earlier, it emerged on the now-defunct website Iron March, from which was also birthed Atomwaffen, and various other more violent, more extremist tendencies and organisations. And that’s ongoing. The Australian fascists draw inspiration from obviously figures like Mosley, Hitler, Mussolini, there’s a whole range, and to some extent part of what they’re trying to do is educate themselves about their own histories, and draw inspiration from those.

But usually the kind of networks that have formed are often more informal, and they’re less about building a particular organisation than they are expressing a particular culture, and cultivating that culture. So that’s also where sites like 4chan, and 8chan, and 8kun, and all the others play a role. And it’s a long-term project of, what could be understood in some respects as a countercultural project, in opposition to ‘political correctness’ and ‘Cultural Marxism’, and all sorts of other things that they imagine dominate Western institutions.

Beyond that you find, among particular ethnic communities, the Ustasha has a presence, Chetniks, this that and the other. Those are fairly minor tendencies, but they’re real, and they draw upon real and ongoing historical connections between fascists in Australia and outside of it.

Derek Johnson: Why do you think that so many, much older, individuals get sucked into those politics, or even Qanon, and all these online conspiracies and stuff, and are some of the most virulent and angry members of these conspiracy groups now?

Andy Fleming: Well, I think it’s, I mean those groups are especially vulnerable in a way that those in other age groups are not. There’s been various individuals who have emerged recently, who have assumed a leading role in propagating conspiracy theories about COVID and so on, and very often those who assume leading positions are already vulnerable, or disposed to conspiracist thinking. And partly that’s because I think is because there’s a real absence of any kind of notion of there being any structural analysis. And also, very often it’s kind of a quasi-religious mentality, where things that happen are cast in terms of good and evil, and a struggle between good and evil, and the important thing for them is to identify who’s good and who’s bad, and who to identify with, and who to cast in the role of the villain, and in that sense it resembles a kind of fairy story, with easily identifiable bad actors and also champions of the good and the just. So it fulfils a certain psychological function, that allows people to have some idea that they’re grappling with the world, but in ways that don’t really challenge their underlying assumptions, which they’re not necessarily even conscious of.

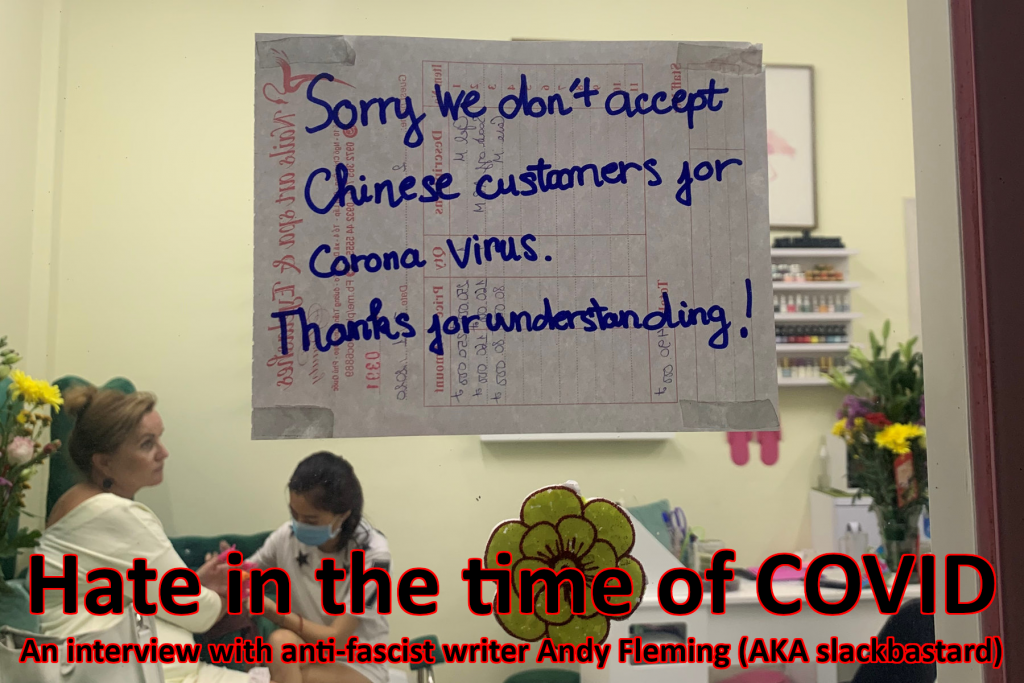

And in terms of COVID and so on, attributing responsibility to the Chinese Communist Party, or George Soros, or whatever, it also draws upon… the long history of anti-Chinese and anti-Asian sentiment in Australia. This conception of the Chinese as constituting this homogeneous mass that is foreign, and hostile, and subversive, it plays very easily into those stereotypes, and actually just adapts them for the 21st century.

And there’s a lot of inchoate rage. It’s often said in the US that support for Trump is a product of economic anxieties, which I’m not sure I agree with really, it’s like a euphemism laughs for racial animosity very often. And it’s wrong also, like many of those who in Australia and the United States, my impression is that it’s not necessarily the case that those who are embracing these ideologies are the poorest. They’re often what might be referred to as petit bourgeois elements.

Derek Johnson: Yeah, we found here in America that most of the supporters for Trump tend to make $40-60k+ a year, so to say that this is members of the working-class, and push this hoax of the existence of an underdog white working-class that we should aim towards to pull them away from Trump is just bizarre. It ignores the fact that this racial resentment has been very obvious since Barack Obama was elected here, and it was obvious that Donald Trump rode Birtherism right into the White House.

But we’ve seen this kind of murky echo-system develop online, where these conspiracy theories are rife, again like what you mentioned, where they’re pushing these conspiracy theories that COVID either originated by the Chinese through recycling old Yellow Perils, or that 5G is spreading it, and there’s evidence to show the Russians are behind that one. Now especially in the US, there’s these wide conspiracy theories going around, saying that even the wearing of masks in and of themselves cause illness, cause you’re exhaling C02, and this is causing a mass hysteria in all of the different states where they pass mandatory mask laws, and you can see all this footage on youtube of clips of all the different people that have been going to public meetings, refusing to wear the masks, and the bizarre stories they’re telling that are completely interweaving all this stuff with Qanon and everything, it’s also what we saw with the protestors that clearly were being paid by employers and were employers themselves, who were out there with guns and everything, calling for the reopening of the economy. Many of them started mixing with the anti-vaxxer circles, then that allowed fascists to recruit from those groups, and many of us have observed that many of the most extreme conspiracists are New Age hippies who a few years ago were flakey liberals who went after Monsanto and stuff, and I’ve dealt with people in family and friends and stuff.

Do you think there’s a relationship between actual far right organisations as such, and this more nebulous echo-system of conspiracy theories?

Andy Fleming: Yeah I do. For a number of reasons, one of which has to do with the historical role of conspiracy thinking. One of the most powerful is anti-Semitic conspiracism. And that was employed when the Tsarist authorities manufactured the Protocols, and published them in the 1800s, whenever it was, that was done consciously as a means of attempting to shift public animosity away from the ruling class and the Tsarist authorities towards a marginalised group. In other words it was functional to the system to encourage these sorts of expressions, and quite a lot of energy was devoted to it. And it was also the case that because the Jews were ascribed all sorts of mysterious powers, their presence was felt everywhere. So bad things happened, who do you blame? Not those responsible for making decisions. This other group instead.

And I’d also say that, in terms of why someone might be interested in these sorts of questions, and why it might be important to oppose fascism and conspiracist thinking, is that even if on the face of it you have people making seemingly ridiculous claims about how wearing masks is endangering the public, however ridiculous it might appear, if it develops political momentum, if there’s an audience for it, it can have really dangerous effects. So it would be wrong to dismiss what would otherwise be characterised as quite silly and unscientific ideas about the world, dismissing them on that basis, what’s important is to recognise how those seemingly ridiculous ideas capture, to some extent, the public’s imagination. And the uses to which those ideas are put.

The first thing that springs to mind, in terms of all this stuff about COVID and so on, is in some respects it performs a similar function to Islamophobia in previous articulations, which is that there’s an obvious audience for these sorts of ideas. And the task of the far right, and some do it quite consciously and explicitly, here’s a group of people who are angry about all sorts of things, what they lack is an explanatory framework, that allows them to understand why these things are happening, and allows them to attribute blame. So for the far right this is very fertile territory.

And the other thing I’d remark is that it’s not difficult, and it’s a very short distance between having these ideas about COVID being bred in a laboratory in Wuhan, or masks being part of some Soros conspiracy, it’s a very short distance between accepting these ideas about COVID being bred in a laboratory in Wuhan, or masks being part of some Soros conspiracy, it’s a very short distance between accepting those ideas as legitimate, and then determining that there’s some kind of nebulous force. And what the far right is trying to do is to name that force, and to draw people towards their own worldview, which is relatively more coherent, and they hope if people will be radicalised in this sense, will then go on to form the kind of organisations that they think are necessary. And if I were a far right actor, I’d be doing exactly the same thing laughs It makes perfect sense to do so.

At the same time, there are other forces, and many of them are grifters, a lot of these New Age characters that you’ve described previously, you know Instagram models. In Australia a more notorious example is someone like Pete Evans, the celebrity chef, who’s assumed some kind of celebrity status, meaning he has an audience of many hundreds of thousands of people who think he’s a great cook. For a period of time he was touting the virtues of the paleo diet, now he’s discovered the anti-vaxx movement, and he’s begun to espouse ideas associated with Qanon. Again this is someone who has, almost needless to say, has no medical qualifications or scientific qualifications of any sort laughs If they had a political perspective, it was fairly limited in nature, and yet you can witness almost in real time the ways in which his public expressions have become increasingly, what I’d consider unhinged. At the same time, he got into trouble with public health authorities in Australia, because he produced a machine which cost I don’t know, $15,000 or something, which is this magic machine that if you bought and you tuned it right, it would address all kinds of illness and maladies, so in a sense, a scam laughs And, if you’re a scammer or a grifter, what you want is a credulous audience, and this audience is entirely credulous.

More broadly, historically speaking, this kind of unhingedness is in a sense reflective of the failure of, let’s say the left or progressive forces as a whole, to produce the kinds of understandings and narratives that might appeal to people, which might actually root their experience in the real world, to provide them with a means of understanding and tackling these issues – to some extent the success of these grifters is testament to the failure of alternatives. So I think these conspiracies need to be debunked, it’s not an easy project, it’s not an easy thing, and it’s a long-term project. A lot of it has to do with public education I think, just providing people with basic economic and medical and political and scientific literacy, so they’re able to engage with these issues on a more rational basis.

Ani White: Do you have any thoughts about how COVID affects organising prospects for left and anti-fascist forces?

Andy Fleming: Well, I wouldn’t claim any particular expertise or insight, one of the obvious impacts is… part of left politics is bringing people together, cultivating community and collective expressions of political and social power, and if people are living, as they must in many places, in relative isolation, that becomes more difficult. And to the extent that these sorts of popular mobilisations rely on gathering people together in numbers, on the streets, obviously that’s an additional concern.

Also it’s significant, in Australia, we’ve had several weeks ago quite large, significantly large, rallies in support of Black Lives Matter, both in terms of expressing solidarity with movements in the US and elsewhere, but also addressing anti-blackness and white supremacy in Australia, particularly in regards to indigenous peoples and deaths in custody, and so on. And they were able to bring together I think, Brisbane and Melbourne witnessed tens of thousands people take the streets. And the organisers of those rallies were very careful to appeal to the public to not attend if they were unwell, to not attend if they were elderly or otherwise especially vulnerable, they arranged for mass distribution of masks, of hand sanitiser, they encouraged social distancing, and put in place a whole range of other measures which meant that those protests, and rallies, and other events, took place in the safest conditions possible. And it seems as though that was relatively successful, so to date I don’t think there’s been any report of any form of transmission as a result of those rallies. Which is a fairly remarkable I think, testament to the ways in which the organisers of those events took these matters seriously, put in place measures to protect themselves and others, and did so in a way that really did bring out lots of people, and lots of attentions to these issues.

I think the kinds of communities that have formed online can be valuable, but they’re also somewhat alienating, they don’t allow for forms of engagement that I think are better when you actually bring people physically together. So I think it’s not ideal in that sense. But again, the US is somewhat exceptional, in the sense that it was a succession of racist murders by police, which obviously has a long history, but yeah it is significant that the killing of George Floyd does actually appear to have been really historically significant, in the sense that it triggered this mass movement, not only in the US but elsewhere. And that also suggests that there’s an underlying body of opinion, and anger and rage, at oppression and exploitation, that you don’t know what it is which will trigger those movements to be publicly expressed in such a dramatic and vigorous fashion. But it does obviously demonstrate quite conclusively that there are serious structural issues, which have not been addressed, and to the extent that they’re systemic, they’re a permanent part of the political landscape, and therefore will always be likely to trigger popular revolt.

To the extent that a lot of political activity has moved online, it also means that this online dimension becomes more important, and also the uses to which all sorts of actors put it. Whether it’s far right agitators producing endless waves of propaganda, the ways in which these online communities form and re-form, it’s possible in that circumstance to devote more energy to monitoring and taking note of these sorts of things. I guess also that for many being under lockdown conditions has been a kind of hothouse, so a lot of people are spending a lot more time online, and social media is critical, sites like Facebook and youtube and so on, have played a fairly reprehensible role in my view, in terms of allowing for expressions of fascism and far right thinking, and conspiracy thinking, and you have a very large audience of relative political initiates, who are suddenly plunged into this world without having any real grounded orientation. They’re subject to all sorts of forces which can take them to all sorts of strange places. And so I think one of the things that this current moment has revealed is just how pernicious has been the role of the major social media platforms, in terms of allowing for, and encouraging, expressions of ideas which could be termed grossly anti-social. So I think it’s a real issue, and one that anyone on the left, or who considers themselves an anti-fascist should really pay a lot of attention to.

Ani White: Has COVID-19 been used to expand repressive powers in Australia? And if so how do we respond to that?

Andy Fleming: It has in the sense that there has been particular legislation introduced which empowers police to issue fines for those gathering in public above a certain number. What’s interesting about that is, it’s been documented by journalists like Osman Faruqi, the ways in which that policing has assumed a racial and a class dimension. So those that are being fined the most, irrespective of the rate of transmission in communities, are those in poorer communities, communities with a higher population of immigrants and so on. It kind of has revealed the racial dimension of policing.

It’s also meant that we’ve had, not necessarily far right forces, but there’s been a series of small protests in opposition to lockdown measures in Australia. One of the leading figures in Melbourne, again you can witness this in real time laughs how they’ve taken, or come from a position of being greatly resentful of having to stay at home, and so on, to try and prevent the spread of the virus, to banging on about the Rothschilds, and so forth. It’s a very short distance.

I guess the other thing is, from my own perspective and that of others, to the extent that the kind of measures that have been introduced and promulgated by the Australian or other governments, about working from home and so on. Here I’d make a distinction between the extent to which these are legitimate, and based on expert medical advice. To that extent it makes sense to follow that advice. This is even in the absence of the legislation that’s been introduced to penalise people for not doing so. I guess it raises the question of what constitutes a legitimate, and illegitimate form of authority and its expression.

The other countries I’m not so familiar, but in the US, the rate of transmission, the rate of death is just extraordinary. And what it also demonstrates to my way of thinking is the outrageous fact that there’s not a public healthcare system in the United States. This the richest empire in history, there’s an enormous need for basic public healthcare, in its absence you have lots of people dying and lots of people suffering. So if you were to make the argument for some kind of comprehensive universal healthcare system, I don’t know if you could point to a better example than COVID, and the incredible damage it’s doing to the US population and society.

So in that sense, if there’s a lesson, it’s the importance of having a public health, and a public healthcare system, that isn’t so entirely dependent on bolstering corporate profits, but instead is addressed to human need. And the importance of asserting, and reasserting, that human health is far more important than profit or the stability of those institutions which are profiting from ill-health. That’s what occurs to me, anyway.

Ani White: In Aotearoa/New Zealand, where I come from, the March 15th Christchurch shooter came originally from Australia. But it also wasn’t surprising that it happened in Christchurch, because that was where the far right had been strongest in New Zealand for some time. So I saw an interesting irony, as someone bridging the trans-Tasman, that whereas a lot of the New Zealand anti-fascist left acknowledged national responsibility for the unchecked growth of the far right, whereas a lot of Australian anti-fascists in my experience at rallies and such, very made the link more with Australian politics.

But obviously it is a trans-Tasman thing, there are trans-Tasman connections, so do you have any comments on trans-Tasman links between the Australia and New Zealand far right, and what implications that might have for our organising efforts?

Andy Fleming: Those links are long-standing, for good reason. I should mention that there was an academic symposium on fascism and anti-fascism in Adelaide, in December of last year, at which a number of speakers from New Zealand came to speak about the history. I understand that the papers that were presented at the symposium will be published next year in an anthology. So that’s a publication to look out for in terms of understanding the historical dimensions of the trans-Tasman links.

In terms of more recent history, I think about, the Australia First Party has links to the New Zealand National Front for the last however many years. I think about the influence of someone like Kerry Bolton as a veteran propagandist, I’ve noticed in recent years some of his writing, particularly his writings on communism and the left and so on, have an audience in Australia. I know that if you look at a group like Right Wing Resistance, with its origins in New Zealand, there was for a period of time an Australian franchise. (One of its members got into trouble a couple of years ago, when they attempted to burn down a church in New South Wales. Significantly, they were subject to a later court action which attempted to apply to them anti-terrorist legislation. As a result of that, I think it was the New South Wales Supreme Court at which the hearing took place, they were designated as the second category of terrorist offence, meaning not necessarily less serious, but less obvious activity).

So there’s some minor organisational links, there’s a shared ideology, and one of the things that I found when the Christchurch killer conducted their massacre in March last year, on sites like 4chan, one of the frequent comments was ‘of course he’s Australian.’ Which also brought to mind the fact that, if you look at forums like Stormfront for example, US-based, but with having participation by Australians and Kiwis, Australia has kind of, in the imagination of the US white nationalist movement, assumed this status of being one of the last remnants of white nationalism. It’s conceived as being a White nation, one which Americans might like to travel to, and live in, if they can.

Ani White: I find that funny living in Melbourne, cause obviously it’s an extremely racist country, but it’s also, Melbourne is an extremely diverse city. I’m living in an area with a large long-standing Vietnamese community, and Greek and Italian community, and yes absolutely Australia had this extremely racist White Australia Policy (an interesting thing being that New Zealand’s very similar White New Zealand Policy hasn’t necessarily been talked about as much), but despite being a very racist country, it’s also actually a country with a large variety of migrant communities, so I always find that very strange, the idea of Australia as this bastion of pure whiteness.

Andy Fleming: Yeah, I mean they’re drawing upon a certain mythology, and there is some basis in truth, about the overall historical direction of Australia. I guess the other thing I’d say is that diversity isn’t uniform, so Melbourne is a relatively multicultural ethnic, racial city, that’s not the case necessarily with Australia as a whole. So there are variations, and it’s important to take that into account. It’s also one of the reasons that Melbourne also has assumed a certain status as being a site of particular cultural and racial degeneracy laughs So when Lauren Southern toured a couple of years ago, there was a headline in the paper, some nonsense she was going on about, nuking Melbourne.

So the kind of things you might think would be interesting about Melbourne, obviously are considered reprehensible by others. And there is a kind of, again it’s somewhat mythical, but it has some basis in truth, that Melbourne’s regarded as being progressive centre. And for that reason, to the extent that it is, it’s bitterly resented laughs That’s also why I like Melbourne.

Ani White: Yeah, it’s a feature rather than a bug, being the site of degeneracy.

Andy Fleming: The other thing I’d add is that Australia’s somewhat peculiar, unlike Aotearoa/New Zealand, Canada, the United States, it was only in 1992 I think that we had the High Court decision, the Mabo decision which recognised the rights of Eddie Mabo and his people in the North of Australia to having some claim to land, but it what it also did significantly was overturn the legal myth upon which Australia was founded, which is still unresolved, in the sense that there has been no formal Treaty process between the Crown and indigenous peoples. What instead we have is a very attenuated form of land rights called Native Title, which is kind of a legal mechanism that was developed by the state in order to deal with these claims. But this is a foundational issue, and while it remains the case, while indigenous peoples what would otherwise be their rights, it’s the other thing to think of it in terms of describing Australia as a racist society, it’s not just relative diversity according to whatever index of its general population, but its actual legal and economic and political infrastructure.

Ani White: Yeah, that is in an important point, in Melbourne which I’ve said is a very diverse area, obviously we’ve had these huge issues of the press attacks on African youth, and casting all African youth as gang members, and very racist policing of African communities, and obviously we’ve seen the campaign against Aboriginal deaths in custody similarly, so yeah. I think the thing I find funny about it is more the idea that somehow it’s a white place, it’s only a white place in the sense of its power structure rather than necessarily the community.

Your blog has been one of the more prominent anti-fascist sources in Australasia, including in New Zealand, and your Facebook has a respectable amount of likes. Can you talk about why the project started, and do you have any ideas about why it’s received the attention it has?

Andy Fleming: The Facebook page I think has just ticked over 24,000 likes. But I think I started that about 10 years ago.

But really, where I began writing seriously on the subject, or any subject, was via the blog, which is roughly 15 years old now. I began that simply as a venue to express my views without having to worry about being censored, or having to write according to a particular standard, basically as a vehicle to express whatever I felt like.

It was also around that time in the mid-2000s that another organising project called Fight Dem Back emerged, as a website, which was a trans-Tasman project, and which I think from memory was inspired by the formation of a trans-Tasman alliance between I think the Australia First Party and the New Zealand National Front, for ANZAC Day or something. Anyway, there was this example of trans-Tasman collaboration on the far right, and as a result anti-fascists in both places decided it would be a good idea to work together to combat it. So around that time, I took notice, and I think wrote a few things, which were received positively, and republished on the Fight Dem Back website.

And it’s 15 years later or whatever, but I guess one of the things I found was that, at the time, perhaps less so now, there was relatively little attention being paid on the part of either the media or scholarship on the far right in Australia, and Aotearoa, and elsewhere. And what material did appear was not especially effective or useful. So I’m not exactly, or haven’t been operating in a crowded field, which is one reason that the blog, and myself, the writing and the other work that I do has assumed a certain prominence, simply through a relative lack of competition really laughs

But one of the reasons I was interested in, and committed to continuing, based on my own experience as an anarchist, I know that any attempt by anarchists to organise in almost any place at any time is going to subject to attack by these sorts of forces, and is. And so, in that self it’s self-defence. It’s important (and maybe we can talk more about this later). So I had reasons to take the far right seriously, and begin to examine it, and write about, in a more serious fashion.

And to do so also from a perspective that wasn’t merely dissolving into support for some kind of liberal multiculturalism, or which failed to address or pay attention to the situation of the far right more broadly, what it reflected about Australian society as a whole, the reasons why a capitalist or patriarchal society might find these expressions of the fascist or far right, why these sorts of societies continually produce this phenomenon. So to try and provide a more grounded vision of anti-fascism and anti-racism, that was at least theoretically committed to understanding these issues in a broader context, and as part of a broader struggle for liberty, equality and solidarity.

Ani White: Yeah, on your blog you wrote a reply to a fairly nonsensical piece, in our view, called Antifa is Liberalism. Can you talk about that?

Andy Fleming: Yeah that was a couple of years ago, I don’t remember the name of the publication where it occurred, maybe it was Retort or something like that?

Ani White: I can’t actually remember. I think it was Marianne Garneau, who writes for Organising.Work, but I think the blog it was written for has dropped now.

Andy Fleming: Oh really. It’s the kind of thing that I think occasionally is worth engaging with, in the sense that what I remember them arguing was, anti-fascism is limited, which I think is correct, and people can read it if they want to, [but] I think it was a miscategorisation, and a misunderstanding of anti-fascism and its sources, and its inspirations, and its goals. So I think it was fundamentally mistaken on a whole range of levels, which I tried to articulate in my response. And I think it was also underestimating the threat, and not just politically, but physically, that fascism and the far right poses to any movement which is progressive let alone revolutionary. And that’s not just a matter of what I’ve read, but what I’ve experienced.

The anti-anti-fascist arguments coming from the left I think are important to engage with, because they do have some purchase, but in my opinion they’re based on a whole range of misunderstandings, and I don’t see anti-fascism as being divorced, in my case, from a broader left project or anarchist project. To me it’s a manifestation of particular political perspectives within a particular domain of action. And if you were to describe antifa as liberalism, that could apply to a whole range, almost any form of left political activity, because it doesn’t in and of itself constitute the revolution. And the important thing is to understand, how do these actions that are taking place in the here and now, either support or hinder the development of a revolutionary project. And that’s not a straightforward question. But to simply dismiss a domain of action as having limitations is fundamentally mistaken.

It also brings to mind another thing, I don’t recall if this appeared before or after the Antifa is Liberalism piece, but there was a discussion between Mark Bray (whom I’ve referred to previously as the author of the Anti-Fascist Handbook) and Chris Hedges, I think it was, the left journalist. And one of the things I noted in that conversation, was Hedges was presenting anti-fascism as ‘the movement’, as the revolutionary movement in the United States, and was pointing out that fighting the Proud Boys in the streets is a different kettle of fish to taking on the US Army. And he was right, but laugh it was to misunderstand the nature of the anti-fascist activity of that moment.

In other words, anti-fascism is a particular political expression, it doesn’t constitute the totality of a revolutionary politics. And it doesn’t claim to! And I think clarity around those questions is important.

Ani White: As you said in the blog post, it’s necessary but insufficient, and the thing I always pose to people who say that is, so what are we supposed to do? So when there are attacks on gay bars, or on migrant communities, what are supposed to do other than organise self-defence and monitor these activities, as a part of our organisation?

And they generally don’t have an alternative, I literally had an argument about this where someone said ‘well we need to organise at the point of production.’ It’s like, okay, I don’t disagree with that, but when somebody attacks a gay bar, does that just mean you go organise a factory and ignore it? These things, they’re not mutually exclusive, and the defence I agree is necessary to ensure that you can do the organising that is actually transformative, that is the organising for something, not just to stop these attacks. But anyway, it was good to see that reply.

We’ve been talking about Australia being a very racist country, which it obviously is (should also acknowledge New Zealand also is a very racist country, you get some people who do this comparison of New Zealand is fine because it’s not as bad as Australia which Isn’t helpful), but for a long time Australia’s Mandatory Detention policy for refugees was exceptionally bad in the OECD. But now we’ve seen similar policies start to be introduced in the USA and elsewhere. What function do you think this punitive treatment of refugees serves, in Australia and elsewhere?

Andy Fleming: Well, I think in many ways, and I’m certainly not the first to remark upon this, but Australia has emerged as a kind of laboratory for various strategies and techniques intended to control population flows, often on a racist and xenophobic basis. The other thing I’d say is that it was the Labour Party, ostensibly the party of the left and of the workers in mainstream Australian politics, that introduced Mandatory Detention in 1992. And this was not in response to a major war, and many thousands of refugees on boats attempting to obtain asylum in Australia. So it has quite a long history, and the fact that it was introduced by a Labour Party, an ostensibly social-democratic but in many respects neoliberal institution now, is significant. And it shouldn’t be forgotten.

And what we’ve had is the further refinement of those techniques of population control over time. So over time those techniques have become even more brutal and even more punitive. And if you want to look at an example of a brutal, punitive system of control of population flows, Australia is a great test case.

So it’s about the ways in which not only particular understandings are developed and cultivated in Australian politics and society, I mean there’s a long history of xenophobia, of fear of the foreigner, of the sense in which the Australian population is constantly besieged, and constantly subject to outside threat. It used to be expressed in terms of Yellow Invasion, without very strong borderls this little white outpost would be endangered by the depredations of the Chinese, or Japanese, or some other racialised Other. And I think the extent to which obviously that feeds into nationalist sentiment, which is contrary to the left notion of internationalism and internationalisation of struggles, of transnational solidarity and so on.

It’s been a profitable system as well, so it’s not just about the way that the state has intervened, but the ways in which markets have been created. These are highly profitable system of repression. Like if you look at the role of transnational corporations like Serco and so on, they’ve got their fingers in any number of pies, both in Australia and elsewhere. And it’s also about creating a market for that sort of adjunct to the repressive state apparatus.

So it provides a political model, it provides an economic model, and a model for other states to employ their own repressive mechanisms. So I’m not at all surprised that Australia has assumed this status. And I think it’s also the case that the Australian state has celebrated this, it’s quite keen to export its technologies to other countries, and other markets. To reiterate, there’s a political dimension, and there’s also an economic dimension, which is important to understand.

And it takes place within a recomposition of the international legal and political order, where to the extent that refugees have rights, and to the extent that they’re enshrined in the Declaration of Human Rights, that was developed in the aftermath of the Second World War, and it was intended, at least in terms of its rhetoric, to try and ensure that the situations in which you have large populations of say Jews attempting to flee Europe, and finding no place to go, and being condemned to death, wasn’t repeated, it wasn’t reproduced. That was meant to be some kind of historical lesson, about the ways in which these rights of human beings to escape war and oppression should be enshrined in some manner. So it also has a corrosive effect upon even establishing the elementary rights to life that were meant to be secured in the immediate aftermath of the Second World War, and the emergent postwar order.

So it’s another example of the breakdown of any notion that human beings have rights, merely by virtue of being alive, and one of those rights is to seek asylum, and to flee from war and persecution. And instead we have developed an essentially neoliberal model for controlling those flows. And Australia has assumed the role of being a laboratory for those sorts of mechanisms.

Derek Johnson: To what degree do you think the mainstream right fosters the spread of the activist far right? For example in the US, we have Trump talking about the Chinese Virus, saying offensive things like Kung Flu etc, inspiring hate crimes against Chinese Americans and other Asian Americans, and giving license to jackboot thugs. Is that sort of thing happening in Australia?

Andy Fleming: It is to a certain extent. Like the Australian Prime Minister Scott Morrison isn’t as active on twitter laughs with his ideas about the world and so on, I think Trump’s kind of at the margins of that sort of thing. But certainly, there were initial attempts, which proved to be ultimately unsuccessful, for it to be understood by the Australian public that this was a Chinese virus. So, several months ago, there was reportage by The Australian, the only national broadsheet in Australia, which attempted to cite US intelligence which was purportedly meant to provide evidence that this was actually bred in some lab in China. And it was ultimately unsuccessful, in the sense that it was eventually understood that there was no real evidentiary basis for this. So there have been attempts to encourage that perception, but in general, it’s not a line that’s been pursued particularly vigorously by Scotty from Marketing.

But there’s probably, outside of those official government avenues, there are elements on the right, in media and elsewhere, who do try to re-construe this virus as being Chinese in origin, being foreign, being malevolent as the Chinese people as a whole are understood to be. So we have witnessed increased reportage and incidence of anti-Chinese and anti-Asian sentiment being expressed, from a small number of assaults, to a whole lot of racist statements being directed to people perceived as being Chinese in Australia.

That hasn’t to date assumed really significant proportions, but at the same time, it’s a difficult question empirically to assess. We have seen the emergence of these figures, whether they describe the virus as being Chinese in origin, the extent to which they associate 5G technology with Huawei, and so on and so forth. Those elements are kind of a permanent part of the political landscape in Australia, they’re often drawn upon by the far right, and the far right has made attempts to reaffirm those kinds of claims, and to cultivate them, and to develop a politics which is anti-Chinese, and pro-Australian (meaning pro-White Australia), so it’s able to draw upon long-standing tropes about the Chinese being a subversive element, the virus being intended to decimate white populations, so in brief yes that sort of thing is happening in Australia, I don’t know that it’s assumed the same form as it has in the United States.

And, I guess the other question that occurs to me is… there’s just a torrent of rhetorical batshit coming out of Trump, it’s like one thing is eclipsed by another. And it’s amusing on the one hand, because it’s just so crazy, it’s the kind of thing, if I heard someone at the pub talking like that, I’d be like ‘oh well, that’s Donald’ laughs that’s the kind of guy he is. But this guy’s the fucking president! So it’s when these ideas become wedded to power that they become really dangerous.

Derek Johnson: Yeah, like talking about injecting bleach into you to fight this virus.

Andy Fleming: Yeah laughs What can you say?

Ani White: Yeah I think it’s interesting compared with Morrison you know, Morrison is more political class. So he did this do-over of himself, where people talked about the daggy dad act, and he did the speech ‘how good are Australians?’ But it is a conventional political class thing, where he put that persona on, almost more like George Bush in a way.

Whereas obviously Trump’s a different thing, where he does not come from the traditional political class, and it’s a strange situation of organic crisis that the US is having, [whereas in Australia] there’s still this extreme conservatism associated with the Liberal National Party, all sorts of similar things like the attacks on the Humanities in universities, similar things happening institutionally, but at the level of the PR or the front people, it’s much more traditional political class, whereas the US is in a particularly strange funk with its leadership.

Derek Johnson: Do you have any comments on Red-Brownism, or the growth of far right ideas on the left?

Andy Fleming: Well, I don’t think it’s a good thing laughs I understand that kind of politics to be a certain capitulation on certain parts of the left perhaps, as well as being a product of infiltration and subversion.

I made reference to the Australia First Party previously, and the extent to which it draws upon a longer tradition of Labourism in Australia, which isn’t quite Red-Brownism but is a form of nationalist politics that has both progressive and reactionary politics. So progressive – and I use these terms broadly – but progressive in the sense that it recognises that it has a working-class constituency, which can and should be protected from the depredations of the market by the State, the national State, which also has an explicit racial dimension as well, and a certain conception of what it is that constitutes the nation and how the State should go around protecting it.

Derek Johnson: So it’s kind of a nationalist populism, that’s both on the right and the left a little bit?

Andy Fleming: Yeah, I think so. I also think about the actual history of the interactions between elements of the left and right in early 20th century Europe and so on, and the extent to which there is political common ground, is often a form of authoritarianism, a form of esteeming political and social hierarchy, of having a certain organicist conception of society, with a place for everything and everything in its place, it’s that kind of appeal to a certain mentality which can be given a Red or Brown flavouring, that speaks to particular needs or ideas on the part of a political community or constituency.

I think about figures like Angela Nagle, and all of the others, their ideas being written about and critiqued, and questions being asked about the ways in which these ideas present themselves as being left or progressive, but whether consciously or unconsciously, conceal a reactionary core. One of the things I found frustrating about Nagle’s book on 4chan and the alt-right and so on [book: Kill All Normies], is it was pretty flimsy, I don’t think it was a great work of scholarship, even if I happened to disagree with its conclusions or methodology.

Derek Johnson: It looks like there’s evidence of plagiarism, and the fact that they didn’t edit the book.

Andy Fleming: Yeah, it looked like, if I were editing it I’d call for some major edits laughs but it hit at the right moment. And I think what it was trying to do was to, part of what I remember reading through it, was it also presented a particular notion of the left which was identified with, or construed to be on the side of something called identity politics, grievance politics, all sorts of things, I don’t think it was historically informed, I think there were a whole lot of assumptions which Nagle failed to address, but even the fact that in that text there was a long quotation from some tumblr account by somebody or other, which articulated 57 varieties of gender or whatever. Which, you know, fine laughs But it was that kind of shallow appropriation of particular expressions identified with the left, which ignored a terrific body of work which takes these questions seriously, which interrogates notions of identity, and which should not be reduced to the kind of caricatures that are relied upon to castigate elements of the left which take other questions seriously.

I find a lot of the critiques that are being produced by those accorded the status of Red-Brown as just, simply being unconvincing. [It’s] very superficial, and it’s a form of trolling culture as well, it’s intended to be provocative, it serves political purposes which I just reject. And the tragedy is there’s a whole lot of interesting questions to be asked about race, and class, and gender, and identity, and politics, and the ways in which they’re engaged with [are] superficial and very unhelpful at best. So, I’m interested in the politics of identity, that’s an important question.

Derek Johnson: We’ve been warning about Red-Brownism for years, and have been covering it on this podcast as it continues to get worse, and I’ve contended that we’re seeing a left-wing flavoured fascism rising in this anti-identity politics, but it ignores existing fascists and fascisms. Fascism is the real threat. It’s a kind of white nationalist democratic socialism metastasising from this Dirtbag Left milieu that we see out of this left trolling culture, of Chapo Trap House etc, all these podcasts and these writers, like the other article [article: ‘Antifa is Liberalism’] mocked antifa from the beginning, and I think that was the first big red flag, and that much of the left missed this strain of fascism I think is a troubling blindspot. Just as much as others in this milieu were failing to see what was happening around them. I thought they ‘can’t see the threat of fascism’ because many of them are Conservative Leftists on the cusp of evolving into Strasserists and fascists. Therefore seeing minorities as enemies, as evidenced by their constant attacks on identity politics, and now their even more fundamentalist embrace of class-reductionism, and so they ‘don’t see’ the threat of fascism as a threat to them, because they’re white, so they see identity politics, political correctness, and this nebulous ‘neoliberalism’ as the real enemy, rather than fascism, and playing into fascist propaganda. And of course, everything they don’t like is neoliberal ideology, conveniently enough, and I don’t think a lot of this is an accident or misunderstandings, I think they are quite cynical and smart, so they know what they’re doing, and a lot of this seems be trolling and gaslighting, and it’s clear opportunists biding their time to side with power. And they see that power is on the far right and the state, so they’re abandoning the left because they see the left as too weak, and I think they’ve tipped their hat with their attacks on open borders, police and prison abolitionism, and from what I can observe they’re basically liberals who hate liberals for being weak, and then they hate the left for centring the marginalised. Do you think that [this is right]?

Andy Fleming: I think so. Assessing the intentions of those who are engaged in this form of trolling culture, maybe some are operating in good faith, and are mistaken, there are bad faith actors as well. I think there’s a kind of nostalgia for what they imagine to have been this ideal political subject. Which was what constituted the basis for the formation of mass movements in the past. And there’s an understanding that identity politics, however they understand it, is disruptive to that, it raises questions, it fractures this identity, or this mass subjectivity. So they regard that as being dysfunctional, and want to decry it, and denounce it, and return to some other idealised subject. That’s a mythology anyway, and it’s also politically fundamentally mistaken.

There is a sense in which the driver is less to do with having an understanding, and a critique of political reality, or engaging in a radical criticism of everything existing, and more about wanting to establish a foundation for a politics which from they think they can in some way profit, and they’re troubled by these, what they understand to be threats. And I suppose, for people of good faith, the kinds of questions being asked that might cause them some discomfort are actually opportunities to explore a whole range of ideas and understandings, that are serious and sophisticated, and add to our understanding of contemporary politics and society. So for them it’s a kind of a missed opportunity. And it’s a failure to engage seriously with what are actually serious and important matters. And maybe that’s moral cowardice, maybe that’s intellectual incapacity, I don’t know, but in either case I think it should be rejected.

And there is a sense in which it also reveals a different understanding of what constitutes a revolutionary project, what are the tasks appropriate today to construct, or to reconstruct a revolutionary movement, and a failure to engage with questions in a way that would open up possibilities for the development of that kind of movement. I guess in my own experience, it’s not the case that all these questions haven’t been engaged with, and there’s a rich body of literature and experience and understanding, which could be drawn upon, and used to good effect. And dismissing what they call identity politics, it’s just a failure.

Ani White: Yeah a lack of engagement with work on racial capitalism, with social reproduction theory, the Catalyst journal which is probably the most theoretically respectable end of this kinda stuff, they wrote an article which attacked the Panthers, but didn’t actually talk at all about the history of the Panthers, it just talked about mainstream Democrat figures who use Black Power language, therefore managed to completely write out one of the very few remotely successful postwar revolutionary groups. And yeah, you’ve got Nagle going on Tucker Carlson, mocking [people in] the DSA… obviously publishing pieces attacking open borders.

In a way it’s accepting a caricature of what socialism is. So people will say socialism or Marxism or what-have-you is just about white workers, and it doesn’t have to be, politics of solidarity across the working-class surely involves for example the historically crucial role of indigenous movements, of migrant workers who make up essential parts of the economy, of obviously Black workers in the US, and all of that is being written out of this account.

Red Wedge, which is quite a good blog, has written some critiques of Nagle, and she responded on the Zero Books youtube, where they said she presents this kind of ‘workerism without workers’, and has this fantasy of the able-bodied worker, and her [response] was ‘yes, of course the able-bodied worker is who I support, because the able-bodied worker is who is able to make social change.’ Which to me is a really fundamental misunderstanding of what class politics is, because any meaningful for example long-term picket or strike action is likely to involve disabled workers, like a picket has to be made accessible, there has to be food, it has to be accessible for people with a range of abilities, so to accept this imaginary of the heroic white worker, who also apparently is old and rural, and that that’s what working-class politics is, it’s not just that it’s class-reductionism, it’s a reduction of class politics, it’s taking class politics from being a universal politics, to being a particular and racialised politics I’d say.

But in the Black Lives Matter movement, which has recently re-exploded and been very inspirational, it’s also triggered thousands to mobilise in Australia. Can you talk about that at all?

Andy Fleming: I can to an extent. What it draws upon in the Australian context, yes there’s a dimension, African Australians are constituted through various communities in Australia, but Blak often spelt B-L-A-K, also refers to indigenous peoples. And obviously, since the late 18th century, there’s been a long history of struggle and resistance to a white supremacist state. This movement has inspired similar mobilisations here, which draw on that history, and express both a commitment to making Black Lives Matter, but making sure that indigenous lives matter as well.

Derek Johnson: So, with all of this in mind, how do we stop fascism?

Andy Fleming: laughs In ten words or less?

Derek Johnson: Yeah, right?

Andy Fleming: Well, if you want to stop anything, you’ve got to understand it first. So, there’s got to be an understanding of what fascism is, how it manifests itself, and paying attention to this being also about addressing one’s own situation, because what you can do about something depends on where you’re at, and when you’re at.

And then also looking at it in terms of being a collective struggle. It’s about how we can stop fascism, who is we? Well, that’s developed through the connections we form with one another in our places of work, our local communities, wherever we happen to be, and wherever we think we can be most effective.

I guess the other question is, well in a certain sense it’s assumed is: why? But it’s important to articulate other values, and other perspectives, and other possibilities for political and social transformation. So it’s not just about stopping fascism for the sake of stopping fascism, although that’s a good thing, it’s about having an understanding of fascism that draws attention to where it comes from and what it represents, and what it is that these ideologies and movements, how they function in order to prevent the emergence of other possibilities, that are more life-affirming, that are freedom-giving, that are egalitarian. So to some extent, stopping fascism is also about not just stopping or disrupting its most obvious manifestations, but also about articulating and realising and embedding other ways of life, other ways of understanding, other forms of social relations, that are egalitarian, and libertarian, and through doing so, encouraging those sorts of expressions, that’s another way of limiting fascism’s potential.

So broadly speaking, the fight against fascism is multivariant, it has many dimensions, but I suppose there’s a kind of sharp edge which has to do with confronting forces that are identifiably fascist, and preventing them from growing, from implementing the kinds of values and practices that they want to. And also is part of a general project of popular self-education, of creating means of liberation, that are based on radically different values, radically egalitarian values, to the extent that they succeed, that’s also a part of the anti-fascist struggle, and that also tends to inoculate societies or communities against fascist political expression.

Ani White: So where can people find your stuff, and is there anything you’re gonna be putting out that you think people should check out?

Andy Fleming: Sure. The main platform I use is my blog. Which is called slackbastard. And you’ll find that at slackbastard.anarchobase.com. I also have a Facebook page and a twitter account. For the last year, my colleague Cam and I have been producing a radio show for local community radio station 3CR, that’s called Yeah Nah Pasaran, it’s a weekly show I think we’ve done 25 episodes so far, and they’re all available for podcasting as well.

One of the things I’m going to be doing in the next few weeks is updating a semi-regular post on the contemporary Australian far right, so I’ll be publishing an updated version of that guide sometime in the next few weeks [blog post: A Brief Guide to the Australian Far Right]. And that will go through, basically in brief form, or relatively brief form, the current state of play on the contemporary Australian far right, and will go into some detail about the dozens of different groups that have attached themselves to the far right in Australia, and bring some of those groups up to date.

Derek Johnson: Right, thanks for joining us.

Andy Fleming: Thanks for having us.